Re-theorizing (the colonial advance of) Capitalism through the lens of Sustainability.

‘There is little question that the worldwide rise of capitalism relied on colonial expansion and that, in turn, the perpetuation of colonialism has been directly enabled by the structures of capital’(Roth 2019, 307). Within the framework of a Western onto-epistemology then, colonization is undeniably linked to the advance of capitalism – both as an ideology and as an economic system. This statement, while assertive, is an excellent entry point into understanding the implications of a colonial epistemicide in the wake of capitalism. Or more to the point, it is an excellent precursor to ask how capitalism has and continue to influence a colonial epistemicide. Equally so, it is a complicated entry point. Not in the least because it involves three concepts that may, at times, seem difficult to grasp; these are, of course, capitalism, colonialism, and epistemicide. In relation to all three, I consequently want to add a disclaimer of sorts: as we move through the complicated (and narrativized) political terrain of pasts, presents and possible futures, I find it useful to keep in mind that there is never a ‘neutral’ context; never an unpolluted and ‘authentic’ origin, and as such there can never be only one way of understanding these terms. From there, I submit that the vernaculars of our fields, practices and/or disciplines maintain different, and sometimes even contrary perceptions and conceptualizations. I will as such preface the following by explaining – if briefly – the terms as they are understood within the framework of my present disquisition. I’ll start with capitalism, but because this is a term that has been discussed extensively over the last decades (by those that are more explicit and in-depth), I will be brief.

Although ‘the impulse to acquisition, pursuit of gain, of money […] has in itself nothing to do with capitalism […], capitalism is identical with the pursuit of profit’ (Greenfeld 2009, 12). Without going into too much detail, and speaking very broadly, I as such understand capitalism to be an economic system that bases itself on the private ownership and appropriation of both the means as well as the profit of production. This comprehension bridges into/onto the next word, which is colonization. The reason being that as a system, capitalism encourages the production of surplus, whether that be a monetary or material surplus, or the amassing of land and property. After all, within the project of (settler) colonization, ‘land is what is most valuable, contested, required’ (e.g, Tuck & Wang 2012, 5). I will pick up on the relation between colonization and land at a later stage. For now, suffice to say that colonialism, and again without too much specificity, is a practice by which one group of people or national state controls, directs, or imposes taxes on other peoples or lands, often subjugating their rule onto others. I think the settler colonization of Turtle Island, or what has been colonially named as Canada or the US, is what comes to most peoples’ mind when thinking of this term. But it also applies in the context of Scandinavia, where my people continue to be defined as Indigenous because we have been colonized and forcefully interned within the colonial Nations states of Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Russia, and whose borders cross the unceded territories of Sápmi. The third concept of note in this text is epistemicide, which is the articulation of a very explicit manner in which knowledge is destroyed. Initially coined by the Portuguese sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2008), epistemicide is a systematic destruction of knowledge – often in the service of political strategies where the intent is to overwrite local knowledge with the imported knowledge systems of the West. As Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012, 64) reminds us in her seminal work on decolonizing methodologies (and academia):

By the nineteenth century colonialism not only meant the imposition of Western authority over indigenous lands, indigenous modes of production and indigenous law and government, but the imposition of Western authority over all aspects of indigenous knowledges, languages and cultures.

This particular quote is an explicit visualization of how epistemicide works in practice, at least in the context of colonization. A colonial epistemicide will often proceed as a result of genocide where entire cultures and societies are systematically erased through violent acts of killing (which is what we are now witnessing in Palestine through Israel’s invasion). An epistemicide may also be achieved through forcefully removing children from their homes – as is the case in both the context of Turtle Island and Sápmi, where Indigenous children – in the past – were forced into residential schools (even if the effects of such are still very much a concern in present time); or as a consequence of missionary work, where ritual and ceremonial practices were banned and replaced with the colonizers organized religion; or, it can be the result of a deliberate destruction of material culture – which we see happen in warfare, when cultural heritage sites are deliberately destroyed (which, incidentally, we now also see inflicted on Palestinian sovereign soil).

Moreover, if we move beyond the context of indigeneity, epistemicide has been invoked in other contexts. The Puerto Rican sociologist Rámon Grosfoguel (2013), for instance, names four specific counts of epistemidices happening within the context of European imperialism in the 16th century (and as such, they helped lay much of the foundation for Western hegemony). They are, in no particular order, the conquest of Al-Andalus, and the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from Europe; the conquest of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas started by the Spanish, continued by the French and the English and still underway today; the creation of the slave trade that resulted in millions being killed in Africa and at Sea, and more, being totally dehumanized by enslavement in the Americas; and the killing of millions of Indo-European women, mostly facilitated by the inquisition and following witch hunts because their knowledge practices were not controlled by men. The reason I bring these four into the equation is because the epistemicides in question were loud, and as such, they were unmistakable, meaning that they are impossible to deny. This form is not, however, the form of epistemicide that I will be discussing going forward. Rather, I will focus on a more silent form of epistemicide. This is arguably a more dangerous form of epistemicide because its silence makes it difficult to spot, which in turn makes it difficult to resist. This brings me back to capitalism, and to another concept, which is that of sustainability.

ENTER STAGE RIGHT; SUSTAINABILITY.

Initially, it might be difficult to see the connection between sustainability and epistemicide, but digging into the origin of the term might clarify the association. Be warned, however, that no matter how often (as an Indigenous scholar of post-colonial theories and Indigenous studies) I have been asked to contemplate the concept of, or better yet, how to decolonize the idea of sustainability, I’m actually not that involved in scholarly explorations of the term. Nevertheless, I have had ample opportunities to consider what sustainability actually means; how do we use it, how do we understand it, and how do we incorporate it into our futures. Reflecting on my process of engagement, I’ll start at (or with) the beginning. According to the Oxford dictionary of languages, ‘sustain-ability’ is the ability for something to be maintained, or sustained, at an even rate or level. Whether we are talking from the perspective of economics, climate and biodiversity, or social and cultural issues, the general idea of sustainability is that products, energy, or processes are made use of or developed in a way that does not cause (too much) harm, but is in fact continuous and ethically renewable. There are of course various points-of-views, and multiple scholars are continuing to debate what ‘sustainability’ is or should be (Parsons et al. 2017; Mazzocchi 2020). I don’t really consider myself to be one of them. Nor do I use the concept in my own work and practice. The reason for such is quite simple, and for some perhaps, somewhat controversial, but I don’t really believe in sustainability. Or better yet, I think that sustainability is a privileged concept, demonstrating how perception matters, and furthermore, how perception is also a question of power and socially approved, but not necessarily equitable, prerogatives. Let me try to break it down.

As a term, ‘sustainability’ was initially developed to conceptualize the long-term and renewable use of natural resources. It was first introduced in 1713 by Saxon tax accountant Hans Carl von Carlowitz (2013) in his treatise on forestry, wherein he discussed the disappearance of forested regions due to mining industry, the consequences following said exhaustion of timber, and finally, the formulation of sustainable forestry practices as a possible solution. This understanding of sustainability interestingly coincides with the birth of what was later named, capitalism.

THE FOUR STAGES OF HISTORY ACCORDING TO ADAM.

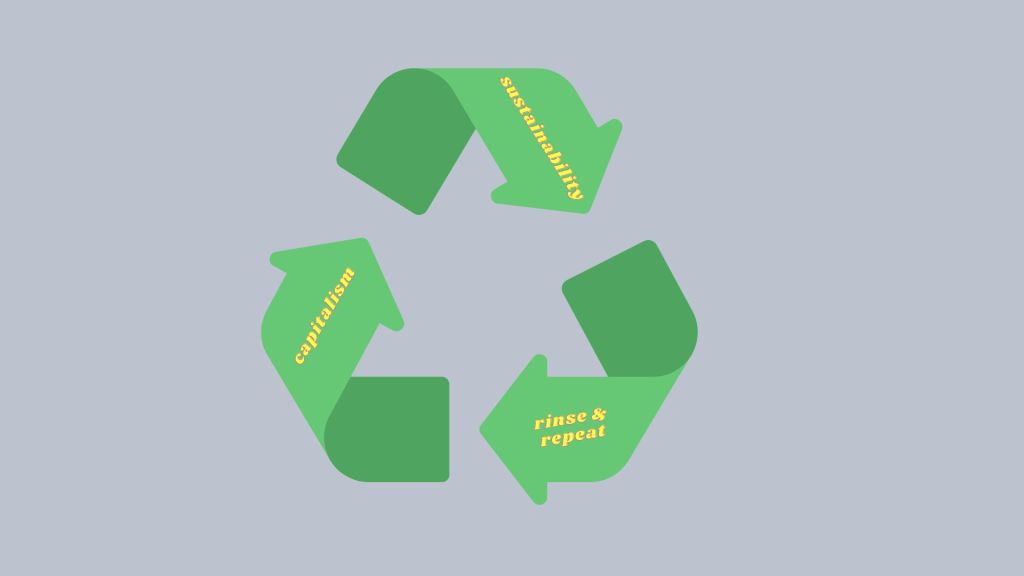

Towards the end of the 18th century, another important treatise is presented when the Scottish philosopher, Adam Smith, launched his ‘stages of history’, which roughly divided humanity’s evolution into four stages of economic and social development. The first and ‘primitive’ stage was the ‘Age of Hunters’, which in Europe had taken place in the Stone Age. In the latter years of this period, what we know as the Neolithic Age, came the ‘Age of Shepherds’, and the ‘Age of Agriculture’ followed soon after. These two stages were considered slightly more civilized, but the height of sophistication only came with the final stage of development, the ‘Age of Commerce’ (Smith 1978a; 1978b). Not surprisingly, this was also the age that Smith himself believed to align with his contemporary (and Imperial) Europe. Indigenous peoples and peoples of color, on the other hand, were typically classified as coming from societies in either the first or second stage (Henare 2008, 68-70). Some has likened Smith’s view with the economic determinism that is so prevalent in Karl Marx’s theory of history from 1867, which mainly focuses on the emergence of commercial societies in western Europe (Meeks 1971, 1976) – what Karl Marx himself described as the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Within this context, and as defined by von Carlowitz, sustainability is what ensures the viable replenishing of the resources necessary to uphold said system. That is to say, the validity of sustainability is only ensured by the upholding of capitalism, and conversely, capitalism is maintained by the existence of sustainability. That is not to say that sustainability in itself is without use or meaning . Nevertheless, the relevance of the term depends highly on how you situate it, or better yet, where you situate your understanding.

INTRODUCING ‘OUR COMMON FUTURE’.

The best example of this, is the 1987 report, ‘Our Common Future’, commissioned by the UN, and led by the former prime minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland. Some might remember how, in the 1980s and 90s, there was an increasing realization amongst the general populations of climate change – although, it was probably not very realistic. We nonetheless started to learn about holes in the ozone layer, the danger of skin cancer from too much tanning, and the increasing pollution from an ever-expanding industrial society. In response to this concern, the UN appointed a World Commission on Environment and Development, and in their report, sustainability became a core tenet, defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Brundtland 1987, 54). This is an understanding that is developed in line with the needs of a Western and capitalistic society, so the report developed its strategy from that perspective, highlighting the need to embed sustainability, not as a solution so much as a necessary amendment to ensure that the quality of life which we had all become accustomed to in the West, could be maintained. Multiple critics from non-Western and Indigenous nations were quick to point out that the report, as such, should be viewed as a Western strategy to influence non-Western countries and nations, stressing that although the report presented a genuine wish to ensure viable industrial development, it also maintained the colonial structures established with the imperial and thus colonial practices of Europe (Bergesen 1988). It might be difficult to understand this critique – at least from within the comfort of Western privilege that so often defines itself as the normative that all should adhere to. A slight reshift, however, reveals that the critique made (and continues to make) perfect sense.

A WORLD OF RELATIONS

If we look to most Indigenous societies, and certainly one that is Sámi, the ontologies that shapes our epistemologies, values and morals are very different from a Western understanding. In its most basic description, Indigenous ontologies – our realities – are structured around meanings and ways of being, of doing and of knowing; connected to cosmological perspectives that acknowledge the world as a living system in which humanity is but a small fragment (Kuokkanen 2005). In this sense, the worlds that we live in and besides are created through an intricate web of connections that extend from many and complex relations between and to people, land, waters, and the multiple entities that we share space with (Sara 2009, 40). In accordance with a Sámi way of life, all these entities are considered morally sensible and capable of subjective will (Joks et al. 2020, 308; Sara 2011, 148). It would nevertheless be a mistake to think that the presence of subjective will is in any way synonymous with the process that occurs when objects, things, and even land sometimes get personified within western ontologies as a way of granting agency. Let me try and explain what I mean by that.

There is a massive difference between subjective will and agency. If I focus on the latter, when objects, things, and land are personified, this is a very useful way to engage in dialogue about their meaning and role in the social network that makes up our societies (Henare 2008, 8) – but always as additions to a human society (See Gell 1998). In that vein, to personify something that isn’t human is to give that something human qualities because having these qualities are perceived to be the highest level of sophistication. Others will perhaps bring up animism, which is the idea that everything has a soul, or more to the point, it attributes a living soul to animals, plants, inanimate objects, and natural phenomena. (e.g, Stringer 1999). Again, there is a but because the soul is a very Western concept. With deep roots in both classical philosophy and Judaism and Christianity, even if the latter two are perhaps far more influential than the former, the soul is once more an example of value being granted to non-human entities by embedding them in what is considered specific human qualities (Swancutt & Mazard 2018, 2). Subjective will, on the other hand, grants everything a will of its own without implicating humanity. That is to say everything has a will of its own and as such, when you enforce your will onto someone or something, you are also subjugating the will of something else (Finbog 2023, 209).

Placing both agency and soul within a discourse of dominion, where non-Indigenous paradigms of research traditionally take point, enforce Western practices, theories, and epistemologies onto Native ontologies. In this way, a ‘pervasive context of settler colonialism’ ensures that non-human beings are fully situated within a humano-centric socio-material context, which inevitably disregard the inherent subjectivity of all matter (Rosiek et al. 2020, 3). Maintaining an Indigenous understanding that privilege subjective will, on the other hand, lays the groundwork for a social structure that never privilege one species on account of another – as Indigenous philosopher, Ailton Krenak (2020, 22), reminds us, ‘I can’t see anything on Earth that is not Earth. Everything I can think of is a part of nature’. When the world is perceived as one of interrelationality, where all are afforded a subjective will, the anthropocentric gives way to an ecocentric framework. Obligated to ecocentric understandings of living, Sámi society in time saw the rise of a system of kinship that honors not only humans as beings of intent, but gives that same consideration to land, waters, animals, spirits and so on. Extending from this world of relations and kinship, specific ethics and philosophies are inevitably developed and these hold certain implications.

For one, similar to many Indigenous nations, Sámi society has an intrinsic comprehension of a duty of care. This is a duty that relies on a collective recognition of connections; expressing that we are already entangled in relations of mutual care with land, waters, other people, and entities (de la Bellacasa 2017:161). In Sámi, the duty of care materializes as the guelmiedahke. Initially an aspect of an ancient and iconographic language, the guelmiedahke represents the idea that there needs to be ‘reciprocity in all my relations’ (Dunfjeld 2006:90, Jernsletten 2009:168). In this way, the guelmiedahke expresses the need and responsibility of sustaining a relational accountability, meaning that we are not simply accountable to ourselves for the choices that we make, but that we also need to be held accountable to all that surrounds us, whether that be land, waters, beings that do not speak, beings that do not breathe, or spirits. When care is understood and employed in this manner, it gives rise to an overall adherence to collectivity, which in turn acknowledges that every choice we make for ourselves, we make for all our relations as well because the choice you make as an individual inevitably implicates the collective. Here we see the biggest difference between a Sámi and a Western understanding, because while the former celebrates community and collectivity, the latter idealizes the individual (Wilson 2001, 177) – how else would capitalism, that helps the few on account of the many, be allowed?

In other words, the guelmiedahke, as a fundamental ethics in Sámi culture, establishes a framework that encourages certain a way of life and it is this way of life that creates our (Sámi) understanding of having a ‘good life’, or what we would term, birgejupmi. Although there is no suitable translation to be found, the term ‘birgejupmi’ implies a specific way of life where there is no abundance, but nor is there any shortage (Guttorm 2011, 60. This reflects a specific (and kinship-based) ideology that encourages a practice of consumption that does not exceed need. As a philosophy then, birgejupmi teaches us that in order to have a good life there must be balance in all things – in your personal life with your interpersonal relationships, but also to the land and waters, other than human beings, and to spirits (Porsanger 2012, 39). As I understand it, birgejupmi takes its place in a circular trinity where it, as a philosophy, invokes a duty of care, which ensures that there is a relational accountability in all things. Claimed as the normative then, this circular trinity of a good life rejects the values of capitalism and in doing so, makes the concept of sustainability redundant. And this is where I get to the point of my contemplation.

To put it bluntly, Indigenous ways of being, what we might term ontology, of knowing, what we might term epistemology, and of doing, or axiology, has always been sustainable, and so the need to conceptualize sustainability was not present in our communities and societies prior to colonization. With the onset of colonization, however, and the capitalistic endeavors of the colonizers, Indigenous ways of life were violently put aside. So whenever the term and concept of sustainability is impressed upon Indigenous societies, but from a Western place of understanding, it is also a reinforcement of the capitalistic values promoted in the West. Perhaps now, there is more clarity (as well as empathy) when looking at the critique of the 1987 report on Environment and development.

To elaborate on that, if we understand capitalism as a system, then sustainability is one of the components that keeps it going – the grease in the machinery so to speak.

Indigenous values on the other hand, as seen and understood within said system, could be considered systemic failures; they are mistakes or oversights in the design, too alien to conform or adapt. Initially, this is an ontological difference, a divergence in both worldviews and ways of living. Due to the disparate power relations that inevitably follows in the wake of colonization, however, this difference all too often becomes a conflict (e.g, Kramvig & Pettersen 2016, 135). Consider for one how most Indigenous worldviews recognize the land as a living entity with a subjective will. To justify the capitalistic expansion into Indigenous lands, a practice otherwise known as colonization, the ontology of the West disregards this subjectivity. Informed and governed by Western ideologies and ideas that enforce control and domination, the land that we live on is instead considered as nothing more than an object for the taking. Something that may be claimed for selfish reasons in the pursuit of financial gain. Or to put it into capitalistic terms, land is both the means as well as the profit of productions. And from here, colonization becomes intrinsically linked with capitalism because land has all too often been the motivation for colonization.

Typically, the premise of colonization is to divest the land from those that already inhabit the space by invoking, what the Indigenous scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2015) defines as the white possessive, a term which draw heavily on Cheryl Harris seminal work, which highlights how property, through settler colonization (and slavery), has been racialized. ‘Possession–the act necessary to lay the basis for rights in property–was defined to include only the cultural practices of whites’ (Harris 1993: 1721). Within Scandinavia, the white possessive materialized in the fact that Sámi people from the mid-1800s were prohibited from buying land, a restriction that lasted well into the latter part of the 20th century (Falch et al. 1994, 95).

CHOOSING THE RED PILL?

But here is the conundrum: The machinery that we have named capitalism, is not a practice that is inherently continuous. On the contrary, it is endless consumption, seemingly tempered by sustainability. Even with the suggestion of sustainable practices, the core values of capitalism remain the same and it is these values that in many ways have left our world on the brink of collapse. In the face of decreased biodiversity – the exception according to the 2019 UN report on biodiversity being on lands under Indigenous guardianship (IPBES 2019) – and the increasingly felt pressures of climate change, efforts to re-theorize, or better yet, decolonize the capitalistic market and the resulting structures, are progressively being instituted. Logistically speaking, this process sees various engagements with the ecological knowledge of Indigenous peoples and communities; often through the lens of sustainability, seemingly asserting values of equity and climate justice. Adapting Indigenous knowledge, however, is anything but. As I have so far discussed (both here and elsewhere), Indigenous knowledge takes part in sophisticated systems, or epistemologies, that have been developed in very localized spaces and over enormous lengths of time (Finbog 2023). The reality of human existence, as perceived within the spatial locations of collective existence together with land, waters, beings that do not speak and do not breathe, and spirits, has – in time – produced specific frameworks for everyday life and practice (which I have tried to make evident by discussing the philosophies and ethics of my own people).

These frameworks, in turn, ensure an equitable way of living that focuses on balance and a decentering of humanity. From within the structures of our current mainstream society (which in large has been founded on capitalistic principles and ideas) these knowledges are deemed ‘sustainable’, and so, in the spirit of sustainability, these knowledges are extracted and forced to fit within a very different worldview where humanity always come first – usually on account of everything else. It might be very critical of me ( although I don’t really think so), but the fact of the matter is that when Indigenous knowledges are co-opted in the name of sustainability, they are severed from the systems that produced them, only to be re-imagined and re-named – often as sustainable practices. The epistemology, in other word, is dispossessed and alienated from the ontology it is beholden to.

Here, we begin to see the silent epistemicide that sustainability encourages. Different, perhaps, from genocide and visible brutality, but equally as effective. A colonial killing still, but now in the name of sustainability, and beyond that, of capitalism. The ‘cognitive imperialism’ that is initiated when Indigenous knowledge systems, teachings, and heritage is accessed by those outside and beyond their provenance is perhaps understandable because it provides a strong counterbalance to the hegemony of the consumption cultures that capitalism produces (Battiste & Henderson 2000, 12-3). Currently, this process is at an all time-high, and yet, the process disregards the very foundation of its presumed salvation. By dissociating from the ontological foundations of the terms and practices that the discourse of ‘sustainability’ has appropriated, the overall achievement continues to be capitalistic excess. As such, the capitalist machinery is simply replicated and re-asserted, and in the process the frameworks of thought that gave initial rise to imperial (and colonially) implemented alienation from Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and doing, continues. Which in turn, runs the risk of further side-lining Indigenous peoples systems of knowledge and our vast multitudes of realities.

In closing, we are left with a variety of questions: Why is there an idea that sustainability, which was created to uphold a specific system, should somehow hold the answer to solving all the issues created by that system in the first place? If sustainability is in duality with capitalism, and indeed holds the key for maintaining a capitalistic society, why would anyone expect that sustainability should solve the problems such a society has created? Indeed, why is it that capitalism, despite so clearly being the root of (existence and) the problem, continues to be in engagement with our socio-cultural and political development? I don’t have the answers, and I won’t pretend that the answers are easy to come by. What I do know is that as long as we maintain the chains of a world-wide subjugation to capitalism, the world we have been colonized to live in will not change. No matter how loud we chant out ‘sustainability’ for all to hear.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Battiste, Marie, and James (Sa´ke´j) Youngblood Henderson. 2000. Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: A Global Challenge. Saskatoon: Purich.

Bergesen, Helge Ole 1988. Reformism Doomed to Failure? A Critical Look at the Strategy Promoted by the Brundtland Commission. International Challenges.

Brundtland, Gro Harlem. 1987. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Geneva, UN-Dokument A/42/427

de la Bellacasa, Maria Puig. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. University of Minnesota Press

Dunfjeld-Aagård, Maja 1989. “Symbolinnhold i Sørsamisk ornamentikk.” Hovedfag i duodji/ master in duodji, Statens Lærerhøgskole i forming., Statens Lærerhøgskole i forming

Dunfjeld, Maja. 2006. Tjaalehtjimmie : form og innhold i sørsamisk ornamentikk. Snåsa: Saemien sijte.

de Sousa Santos, Boaventura 2008. “Introduction.” In Voices of the World (Reinventing Social Emancipation Toward New Manifestos), edited by Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Pp. Xv, Verso Books.

Falch, Tor, Norge Justis- og politidepartementet, and Samerettsutvalget. 1994. Bruk Av Land Og Vann i Finnmark i Historisk Perspektiv : Bakgrunnsmateriale for Samerettsutvalget. Vol. NOU 1994:21. Norges Offentlige Utredninger. Oslo: Statens forvaltningstjeneste, Seksjon statens trykning.

Finbog, Liisa-Rávná. 2023. It speaks to you : making kin of people, duodji and stories in Sámi museums. DIO Press.

Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and agency : an anthropological theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Grosfoguel, Ramon. 2013 “The Structure of Knowledge in Westernized Universities: Epistemic Racism/Sexism and the Four Genocides/Epistemicides of the Long 16th Century.” Human architecture 11.1: 73–90.

Guttorm, Gunvor. 2011. “Árbediehtu (Sami traditional knowledge) – as a concept and in practice.” In Working with Traditional Knowledge: Communities, Institutions, Information Systems, Law and Ethics: Writings from the Arbediehtu Pilot Project on Documentation and Protection of Sami Traditional Knowledge edited by Jelena Porsanger, Gunvor Guttorm pp. 59-76. Guovdageaidnnu: Sámi Allaskuvlla.

Haakonssen, Knud. 1981. The Science of a Legislator: The Natural Jurisprudence of David Hume and Adam Smith, Cambridge University Press.

Hansen, Lars Ivar, and Bjørnar Olsen. 2004. Fram til 1750. Vol. [1], Samenes historie. Oslo: Cappelen akademisk forlag.

Harris Cathy. 1993. Whiteness as property. Harvard Law Review 106(8):1710-1791

Henare, Amiria. 2008. Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange: Cambridge University Press

IPBES. 2019. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo (editors). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany

Jernsletten, Jorunn. 2009. Bissie dajve : relasjoner mellom folk og landskap i Voengel – Njaarke sïjte. PhD, Tromsø: University of Tromsø.

Joks, Solveig Liv Østmo, and John Law- 2020. ‘Verbing ‘Meahcci’: Living Sámi Lands,’ The Sociological Review 68, no. 2

Kramvig, Britt & Margrethe Pettersen. 2016. Living Land – belove as above. Living Earth Fieldnoted from the Dark Ecology 2014-2017, Sonic Act, 131-141.

Kuokkanen, Rauna. 2005. “Láhi and Attáldat: The Philosophy of the Gift and Sami Education.” The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 34, pp. 20-32.

Krenak, Ailton. 2019. Ideas to Postpone the End of the World. House of Anansi Press.

Mazzocchi, Fulvio. 2020. “A Deeper Meaning of Sustainability: Insights from Indigenous Knowledge.” The anthropocene review 7.1: 77–93.

Meek, Ronald. 1971. ‘Smith, Turgot, and the “Four Stage s” Theory’, History of Political Economy, 3:1, pp. 9–27.

1976 Social Science and the Ignoble Savage, Cambridge University Press

Moreton-Robinson. 2015. The white possessive : property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

Parsons, Meg, Johanna Nalau, and Karen Fisher. “Alternative Perspectives on Sustainability: Indigenous Knowledge and Methodologies.” Challenges in Sustainability 5.1 (2017): 7–14

Porsanger, Jelena. 2012. “Indigenous Sámi religion : general considerations about relationship. In The Diversity of Sacred Lands, edited by Josep-Maria Mallarach, Thymio Papayannis and Rauno Väisänen in Europe, pp. 37-45. Gland: IUCN

Rosiek, Jerry Lee, Jimmy Snyder, and Scott L. Pratt. 2020. “The New Materialisms and Indigenous Theories of Non-Human Agency: Making the Case for Respectful Anti-Colonial Engagement.” Qualitative Inquiry 26 (3-4), pp. 331-346

Roth, Solen. 2019. “Can Capitalism Be Decolonized? Recentering Indigenous Peoples, Values, and Ways of Life in the Canadian Art Market.” American Indian quarterly 43.3: 306–338.

Sara, Mikkel Nils. 2009. ‘Siida and Traditional Sami Reindeer Herding Knowledge,’ The Northern Review (Whitehorse) 30: 40.

2011. ‘Land Usage and Siida Autonomy,’ Arctic Review 2, no. 2

Smith, Adam. 1978a. Lectures on Jurisprudence, ed. R. Meek, D. Raphael, and P. Stein, Oxford: Clarendon Press (referred to as LJ).

1978b. Early Draft of Part of the Wealth of Nations, in Smith (1978a) pp. 562–81

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies : Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books, 2012.

Swancutt, Katherine and Mireille Mazard 2018, eds. Animism beyond the Soul : Ontology, Reflexivity, and the Making of Anthropological Knowledge. New York ; Berghahn Books,

Stringer, Martin D. 1999. «Rethinking Animism: Thoughts from the Infancy of our Discipline». Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 5 (4): 541–56

Tuck, Eve & Yang, K.. 2012. Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor. Decolonization. 1.

von Carlowitz, Hans Carl. 2013. Sylvicultura Oeconomica, Oder Haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung Zur Wilden Baum-Zuch. Oekom, [Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar]

Wilson, Shawn. 2001. ‘What Is an Indigenous Research Methodology?’ Canadian journal of native education, Vol.25 (2), pp. 161-17

Winch, Donald. 1983 ‘Adam Smith’s ‘Enduring Particular Result’: a Political and Consmopolitan Perspective’, in I. Hont and M. Ignatieff (eds), Wealth and Virtue: The Shaping of Political Economy in the Scottish Enlightenment, Cambridge University Press, pp. 253–269.